Hello, hello, and look! over two years have passed. What have you all been up to? OH YES, THAT.

Passing swiftly over THAT (and the three books I’ve written since the last time I attempted to remember my password for WordPress OH HOW TIME FLIES WHEN YOU CAN’T LEAVE THE HOUSE), I’m back for the purposes of uploading some recipes.

The absolutely brilliant Kathy Hipperson and I did a few videos for English Heritage during lockdown, as we couldn’t film the wildly popular The Victorian Way videos – many of you will know her as Mrs Crocombe on them (I’m a sidekick aka the historic consultant – they are made by a small but dedicated team). For the platinum jubilee they asked us to do something similar. I’m afraid to say we balked at the idea of using our phones to film ourselves having fun in the kitchen as it was a horrific amount of work and we were pretty bad at it. So we used a proper film maker and the results were much more professional, yet still very us. (Thank you, Abs – you can see more of his stuff here). The video was initially for members only, then went live to everyone – hoorah! You can watch it here.

Anyway, we’ve been asked for more clarity on the recipes, so for those of you who aren’t English Heritage members and didn’t get the full works… here they are:

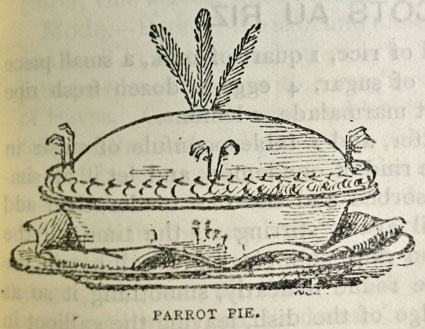

Henry III: A great pie

Drawn mainly from Harl. 4016 (see Austin, Thomas. 1888. Two Fifteenth Century Cookery Books) with additional tweaks from various other 14th and 15th century sources.

Serves 10 (ish)

Enriched shortcrust pastry: 500g (1 lb) flour, 200g (7oz) butter, 2 tsp salt, 2 whole eggs, 2 tbsp ice cold water.

Crumb the flour, butter and salt. Mix the eggs with the water. Add the liquid to the flour mix and blend to form a stiff pastry which comes together and isn’t sticky. Add a little more chilled water if required. Form it into a rough rectangle and chill for at least 30mn. (NB: our pastry used a mixture of stoneground wholemeal, plain and a little rye to replicate medieval landraces, but you don’t have to be this nerdy).

Forcemeat: 750g (1 ½ lb) of minced mixed meats (the original uses beef mixed with pork, veal or venison: we used venison and pork sausage meat), 2-3 tbsp red wine vinegar, a large handful each of currants and chopped dates, ½ tsp each of ground pepper, cinnamon, ginger, salt, ¼ tsp of ground cloves, mace plus a little ground saffron.

Mix all of the above together. Go easy on the spice if you aren’t certain if you’ll like them.

Stuffing: 4 chicken breasts, ½ tsp ground saffron, 4 hard-boiled egg yolks, ¼ tsp each of ground mace, cloves and black pepper (cubeb pepper is even better if you can get it), 1-2 more handsful of chopped dates.

Glaze: 1 whole egg, beaten well with a pinch of salt.

Butter (really well) a 21cm round springform cake tin or 25cm x 10cm rectangular pie mould. Remove your pastry from the fridge and cut off about a third (enough to form a lid later). Form the pastry into a rough bowl (if using a round tin) or box (is rectangular). Place it in the cake tin, and use your hands to gently push the pastry out and up to line the tin fully, with no tears. Allow at least a 4cm overhang. Trim. You can also line the tin more conventionally, by rolling the pastry and fitting it to the tin, but we use this, historic method, as it means the pastry is less likely to spring a leak.

Use the forcemeat it to line the bottom and sides of the pastry.

Dice the chicken and mix it with the saffron. Put this into the pie, and then add the spices and a layer of crumbled egg yolks, along with the dates. Moisten with a little water.

Fold the edges of the pastry back over the filling, pinching them to form a sharp edge. Roll out the reserved pastry, trim to fit, moisten the edges and put the lid on. Crimp or pinch to seal. Make a vent by cutting a hole in the lid and either use pastry offcuts to make a pastry chimney, use a roll of foil, or a large piping nozzle to alleviate overflow (boil out).

Decorate the top with your family crest made from pastry (other decorative schemes are also available). Glaze with egg wash. Chill. Glaze again.

Bake for around 3 hours at 150C, checking the temperature with a prob thermometer inserted down the air hole to ensure it reaches 75C.

Remove from the oven and chill. Serve cold. (You can also serve this hot).

James I & VI: sugar plate

Based loosely on Plat, Hugh. 1602. Delightes for Ladies.

Makes an enormous amount, but it tends to all get eaten.

3 tsp gum tragacanth, 2 tsp lemon juice (about ½ a lemon), 1 tbsp rosewater (not the concentrated stuff in oil – or if that’s all you can get, use about ½ a tsp of that and 2 ½ tsp water), 500-600g icing sugar, 1 small egg white

Steep the gum trag overnight in the lemon juice and rosewater until it forms a thick paste. Sieve the icing sugar, and put 500g of it in a bowl. Add the gum trag, and beat the egg white to brwak it up. Add most of it. Mix to form a malleable, mouldable, paste. If it’s too dry or too wet, use the leftover egg white and remains of the sugar to adjust it.

Store in beeswax wrap covered with a damp cloth to stop it drying out and use a little at a time. Work quickly, using a mixture of icing sugar and cornstarch (cornflour) to ensure it does not stick. You can use the paste to roll out and cut out shapes, to make plates, to make pieces of architecture to join up to make buildings, or anything else you fancy. Colour up as desired (not blue: a stable and edible blue isn’t a thing in the 17th century). Leave to dry on silicon or greaseproof paper spread with a layer of icing sugar and starch for at least 12 hours in a warm, dry place.

George III: Queen Cakes

Adapted from Maria Rundell. 1806. A New System of Domestic Cookery

Makes about 50 cakes (i.e. you may wish to halve it – but they are very popular)

4 large eggs, 450g (1lb) each plain flour, caster sugar, salted butter and currants, 1 tbsp orange flower water (or 1 tsp if concentrate in oil), 2-3 tbsp caster sugar and butter for lining the moulds.

Separate the yolks and whites and beat them until the yolks are pale and frothy and the whites are at soft peak. Cream the butter and sugar. Add the currants and flour and then beat in the yolks and the whites. Beat by hand for an hour(!) or in a stand mixer on high speead for around 10-15mn until the mixture is a very pale yellow. Beat in the orange flower water.

Grease some small moulds, ideally heart-shaped, and line them with sugar (this ensures a crisp crust). Put about 1 tbsp batter into each mould, smooth the tops and sprinkle caster sugar on top. Bake for about 25mn at 160C until pale golden brown. Turn out and cool. Repeat.

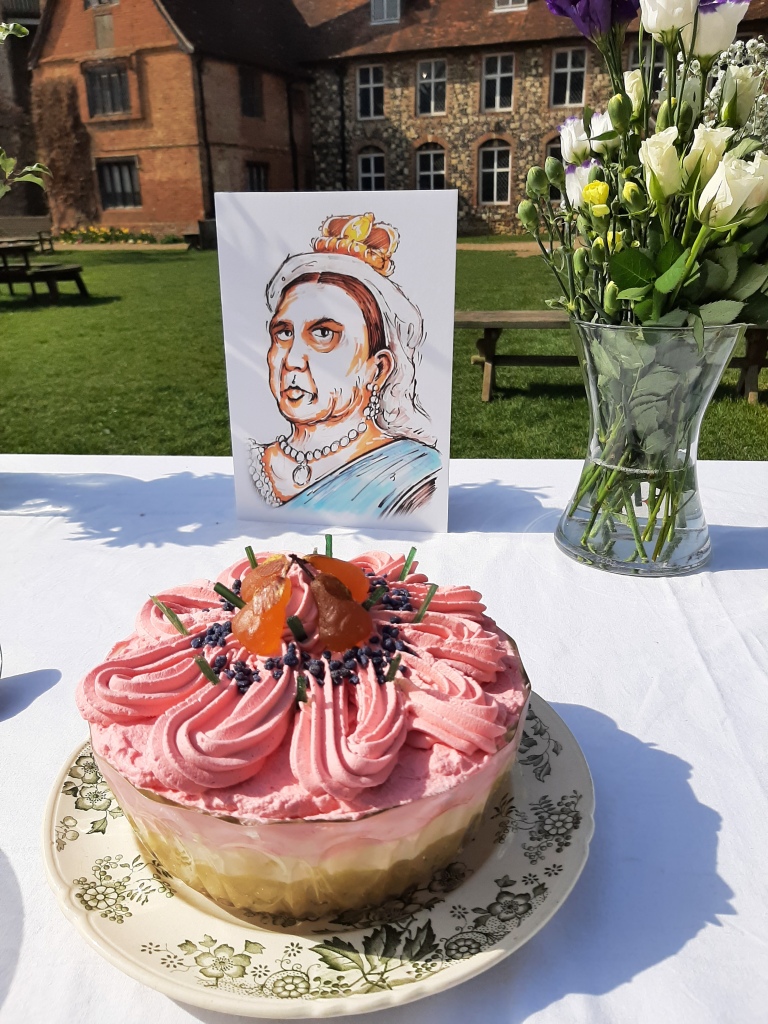

Victoria: Apple Trifle

Based on Anon [Payne, Arthur G]. c.1875. Cassell’s Dictionary of Cookery.

Serves 8-10

Apple purée: 12 eating or dual purpose apples (cox or Braeburn type ideal), 2 tbsp demerara sugar, 2 tsp finely grated lemon zest, 1 tbsp brandy.

Peel and core the apples, dice them and put them in a pan with 2 tbsp demerara sugar and 2 tbsp water. Bring to the boil, and simmer till soft, purée them or mash with a masher, then mix with the grated lemon zest and brandy. Set aside to cool.

Custard: 300ml (1/2 UK pint) cream, 300ml (1/2 UK pint) milk, sugar to taste, 3 egg yolks, 2 tbsp cornflour.

Simply mix all of the ingredients together, whisk well and then bring very gently to the boil, whisking continuously and scraping the bottom so that the cornflour does not stick. When it thickens to the consistency of double cream, remove from the heat, and cover with a round of baking parchment to stop a skin forming as it cools.

Cream: 600ml (1 UK pint) cream with 50g (2 oz) caster sugar, and when it forms soft peaks, slowly add 75ml (3 tbsp) of sherry. You can, for Victorian fun, colour the cream pink using powder or gel colouring.

When all the preparations are cool, layer them into a glass bowl. Start with the apples, then the custard, then the cream. To finish, fill a piping bag with the cream, and pipe it on top attractively.

Decorate with apple jelly, candied fruit, crystallised cherries, angelica, or candied (or real) flowers.

Elizabeth II: Poulet Reine Elizabeth (Coronation Chicken)

Adapted from Rosemary Hume’s 1953 recipe, published in Hume, Rosemary and Constance Spry. 1956. The Constance Spry Cookery Book.

Serves 6-8 or more as part of a large buffet

Chicken: 1 small (1.25kg) chicken, a mirepoix of diced carrot and celery, a little salt, a bouquet garni.

Put the chicken in a pan, cover it with water (just), add the mirepoix, salt and bouquet garnis and bring to the boil. Turn right down and poach for 15-20mn. Cool in the liquid, then remove the meat and dice. Set aside.

Sauce: ½ tbsp neutral oil (sunflower or rapeseed), ½ tbsp minced onion, ½ -1 tbsp curry paste, ½ tbsp tomato purée, 65ml red wine, 65ml water, 1 bay leaf, a pinch of sugar, 1 tsp lemon juice (plus more, to adjust seasoning if required later), 1 slice of lemon, seasonings, 4 dried apricots, soaked in hot water for 30mn and then minced finely, 200ml very good quality mayonnaise (we made our own*), 2-3 tbsp whipping or double cream.

Fry the onion in the oil on a medium heat for 3-4mn. Add the curry paste, puree, wine, water, bay, sugar, lemon juice and slices and bring to the boil. Simmer uncovered for 10-15mn to reduce, then strain, season to taste and cool.

Make some mayonnaise, and then whip into it the strained, cooled, sauce. Add the minced apricots. Taste and add more lemon juice if needed. Add the cream.

Fold just enough of your sauce into your chicken to coat each chicken piece.

Serve on a round of rice salad made with boiled rice, peas, diced cucumber, mixed fresh herbs and a French dressing (vinaigrette).

*If you want to make mayonnaise, it is very easy. It’s just one egg yolk, ¼ tsp salt, a squeeze of lemon and a ½ tsp mustard, mixed together. Then you very gradually add 250-300ml neutral oil, whisking or beating with a spoon or spatula all the time, until it emulsifies. Last thing, a tbsp of vinegar, preferably tarragon vinegar (just steep fresh tarragon leaves in white wine vinegar for at least 3 days – I keep a jar permanently in the fridge).