With the Waitrose Good Food Guide out last week, the PR machine behind it has been seeking hooks for newspapers. The main story I’ve seen centres around the apparent rise in informality in fine dining establishments. The staff at the two-starred Hibiscus are doing away with their ties, and various chefs are quoted as endorsing a move away from leather-clad menus and toward a recognition that jeans are acceptable eating-wear. Elizabeth Carter, the editor of the GFG, suggests it indicates the rise of fine dining as an activity for ‘ordinary’ people, enjoyed by those who partake much as others would enjoy a football match, or a visit to the theatre. She points out that (some) high-end restaurants have become a destination, with a meal to be saved up for, anticipated, savoured at the time and afterwards. Tied, for some at least, to the habit of taking photographs of every dish, and live-tweeting the entire experience. Restaurateurs who don’t relax the rules for this new, more free-wheeling set of eaters, risk alienating potential customers. But, as the brief furore over photography in restaurants last year shows, while there are those who want eating out to be an extension of walking down the street, there are others who still want dining, at least at the upper end, to be something special, marked out by a degree of reverence, of privacy. The kind of experience you get somewhere like Le Gavroche: you feel cocooned and cosseted, wrapt up in a room full of food and from which you emerge, blinking, and a little bit poorer. Done well, as at Le Gavroche, I love a bit of formality. I like dressing to go out for dinner: the rituals of posh frock, make up, and maybe even heels, add a certain mystique to my dinner and make the experience into far more than just stuffing my face. Done badly, and I have undergone achingly pretentious levels of formality, mainly, it must be said, in France, and I want to throw my cutlery at the waiter and start dancing on the tables.

I think there’s room for a lot of different levels of formality. There always have been. Our current notions of what constitutes ‘formal dining’ haven’t really changed since the 19th century. Then, they made perfect sense. A restaurant meant something specific, as opposed to a chophouse, an inn, a hotel, a café, or a tea rooms. The restaurant was something intrinsically French, upper class and elegant. The term emerged from 18th century France, and it’s generally agreed that the first establishments to call themselves restaurants did so because the set out to ‘restaurer’, to restore, in this case both health and palates, jaded by the rather brilliant, but at times excessive, delights of upper class French cuisine. The French were probably influenced by the existence of a long English tradition of eating out for pleasure: nearly all 17th and 18th century diarists depict eating out, both in public eating houses or in clubs, as a regular activity. Try Dr Johnson, Pepys, or Thomas Trussler – and then there’re the number of cookery book authors who proudly declare that they are the cook at [insert inn name here]. Either way, the restaurant quickly became established, and eventually they started to open under that name in the UK. They were always distinct from other types of dining out of the home. The cuisine was ‘recherché’ – fashionable, modern, above all else, French, which was rapidly being established as the aspirational ideal for the ever-rising middle class. The dining style was also markedly different from dining at home. Restaurants were known for being places which favoured the lone diner, allowing, as they did, a free choice of dish from a range on offer. That range could be very long indeed, and the diner needed neither to carve, nor to help serve out, as was often still the case in a domestic environment throughout the 19th century.

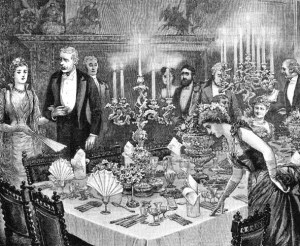

Dining in a restaurant, therefore, was akin to dining in an idealised home, without the hassle of negotiating with one’s cook, and was deliberately removed from the informal environment of an inn or chophouse. Eating at home was beset with social pitfalls. The late Victorians had codified dinner to a degree where table manners could be neatly packaged, written down, and sold to wannabe socialites as their ‘in’ to polite society. Of course, it was largely rot. One commentator, ‘fin bec’ commented narkily that ‘an etiquette book in the possession of a diner is virtually a pièce de conviction’. In other words, if you need a guide to doing it, you aren’t the right type of person to be invited in the first place. In late Victorian society, the almost infinitesimal divisions between social groups could be negotiated through manners, and dinner was a crucial area for their observance.

The so-called traditional rules of restaurant dining, therefore, reflects a society obsessed with social acceptance, and determined to invent ever more ways of testing it through etiquette. Do we need to sit down to a place setting hemmed in by ranks of silver cutlery? No. Do we have to worry over cutting or tearing the bread? No. Does it actually make a blind bit of difference which glass we drink the wine out of? Hell no (though jam jars are a different matter and anyone serving me a beverage in a jam jar deserves to go straight to culinary hell). But it did matter; really, it did. And to some people it matters still. Are they old fashioned? Perhaps. Should we push their views to one side and rush to embrace a more informal approach? I don’t think so. If you chose to dine in jeans, and pick your menu using marbles, good on you – as you masticate, you will be in the company of like-minded people. But if you choose to wear a tie, and expect a menu which feels reassuringly heavy*, good on you too. Just like a good Victorian, how you dine reflects who you perceive yourself to be, and that, surely, is always ok.

*That said, it is never ok to have a menu which doesn’t have prices on for the lady, and does for the chap. Just saying.

Further reading:

John Burnett (2004) England Eats Out, 1830-present

Rebecca Spang (2000) The Invention of the Restaurant

Michael Symons (2001) A History of Cooks & Cooking