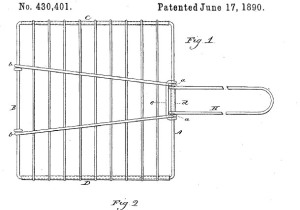

The new series of The Kitchen Cabinet is here – yay! In keeping with the bank holiday tradition of having a ridiculously late lunch of half cooked meat with a tang of firefighting fluid, we discussed barbecuing. I brought one of these with me.

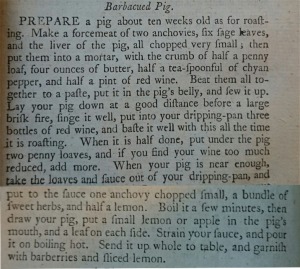

I’ve been asked a few times about the history of barbecuing: where it originates, why it’s so inexplicably gendered, and why so much of the stuff turned out on BBQ’s in the UK is crap (ok, I made that last bit up, but I had a fairly traumatising occasion last year involving poultry, charcoal, and the clear need for a meat thermometer. It could have ended in A&E). It has a long, complicated, and increasingly disputed history. The OED suggests etymological origins from Portugal, with the word itself entering the English language by the seventeenth century. You can find early English recipes in most eighteenth century cookery books, such as this one, from Henderson (c.1800):

Here, the specificity doesn’t lie in the technique – it’s just roasted meat – but in a mixture of the ingredients, the basting, and the use of the contents of the drip pan to make a sauce. We’d recognise the application of direct heat to a lump of meat and the dousing in a spicy sauce as being part of modern day barbecuing. Elsewhere, the term is used to indicate the grilling of meat over a fire on a platform or piece of apparatus constructed for the purpose. Again, something we’d sort of recognise today.

(Incidentally, grilling is in in the old English and modern American sense of heat from below, rather than modern English heat from above. Today we use grill for top heat, Americans use broil. We used to use broil for top heat too. Etc.).

Barbecue as a term continues to crop up throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth century in English-authored cookery books, and it would be plausible to see a link between the fairly basic techniques of grilling and roasting on open fires with some form of sauce, and the development of modern BBQ, which is overwhelmingly associated with countries which were colonised and/or opened up by westerners in the same period. Australia, New Zealand and, of course, America, in particular the Deep South, also have the benefits of having a climate which makes the development of BBQ techniques and recipes not only feasible, but necessary – put simply, in a country like Britain, where you can reasonably only BBQ three or four times a year, BBQ can only ever remain a bit of a novelty. Elsewhere, it’s a quotidian cookery method. There’s a strong argument, however, that BBQ was (and is) a pretty low-tech way to cook, and that, for that reason, in America, it was the very poor, especially rural poor who really elaborated the techniques and flavours. And yes, very poor, and rural poor, in the Deep South, means slaves and their descendants. There were, of course African antecedents – but let’s face it, every culture armed with food and fire and a basic ability to construct a bit of kit has traditions involving open fire cookery. There’s an excellent article on this subject by Michael Twitty from The Guardian here, and a piece on the tension between modern, white BBQ champions and the real heritors of many of the historic aspects of BBQ on the BBC here.

BBQ, then, historically, is just cooking. English recipes clearly show that, even if its origins may have been in outdoor, open-fire cookery, the term was quickly applied to kitchen-based cookery. In America, where it stayed outside, it was still everyday cookery. So how on earth did we get to a stage where, in the UK at least, it has become a weirdly gendered, and very specific style, of ruining your lunch?

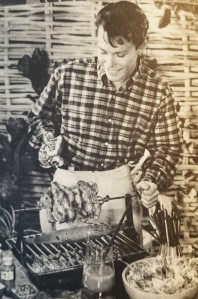

I think part of it comes down to open fires disappearing from our homes. BBQ doesn’t have much of a presence in formal food writing, at least, in the twentieth century, until the 1960s. Of course, many homes still had open fires for heating at that point, but fires for cooking on were increasingly rare. Rare, mildly dangerous things, especially those involving physical labour and special gadgets aren’t naturally gendered – nothing is – but sadly they tend to be written about in gendered terms and marketed toward men. By the late 60s and 70s, when BBQ recipes and techniques were starting to appear in cookery books, the gender division was already clear, along with the cunning ploy of selling extra kit to naive cooks. Here’s Marguerite Patten’s Book of Savoury Cooking (1961), and The Good Housekeeping Camping Caravan Cookery Book (1978):

Pshaw, I say. It’s all a load of rubbish, I hear you cry! Well, of course. We have absolutely no need for heaps of special tools for cooking stuff in a way in which was the only way of cooking stuff for quite a lot of centuries. A modern day standard charcoal BBQ is just a chafing stove. Here’s one at Kew Palace.

Gosh! A grill with charcoal in, and stuff cooking on top! Hmm. Which brings me to my last point. I have had some really good food cooked on BBQs (I’m not even going never the idea of gas BBQs here, by the way – just, no). I’ve even had good food cooked on BBQs in the UK. But generally it’s still a heady mixture of raw and burnt, firelighter flavoured and served with poor quality bread baps and sodding iceberg lettuce. But how to better the British BBQ experience? Well, if you think of your BBQ as a chafing stove and basic roasting apparatus, it does rather help. Here are my top (historically influenced) tips:

1. BBQs enable most of us to get as close to proper roasting as we will ever come. If you’ve a kettle BBQ, you can use indirect heat to roast a joint. If you’ve a more basic beast, buy a spit mechanism (about a tenner in French supermarkets from April to September). Then you can do this:

2. It’s a grill. Grill stuff. Hence the gridiron I opened with. Use the same techniques you would use in a top heat grill attached to an oven. Presumably you don’t usually serve half raw chicken legs from the grill, right? (Sorry – honestly, it was a terrible evening and the memories just burn).

3. It’s a stove. You can make sauces. Like this:

4. Buy a meat thermometer. Please.

For more BBQ fun, the podcast of The Kitchen Cabinet is available via iPlayer, iTunes and all the usual suspects. Or the dedicated webpage is here.